The thin fellow you saw in the post office the other day with that

worried look might well have been one of the millions of stamp

collectors in this country. He has had a harrowing year a year (1948) trying

to keep track of the special stamps that have rolled from the presses

in the U. S. Treasury’s Bureau of Engraving and Printing, Washington, D.

C.

The last Congress may go down in history as the “Stamp Act” Congress.

By congressional authorization, its members sponsored a new stamp on

the average of every other week in 1948. Stamp dealers groaned. Stamp

collectors groaned. Officials of the bureau groaned loudest of all, but

Congress went happily on its way paying tribute to everything from the

poultry industry to the Gettysburg Address.

The bureau has the big, job of turning out some 20 billion postage

stamps a year, (stamped envelopes are subcontracted) and billions of

federal tax stamps such as are found on packages of cigarettes, playing

cards and many other items.

|

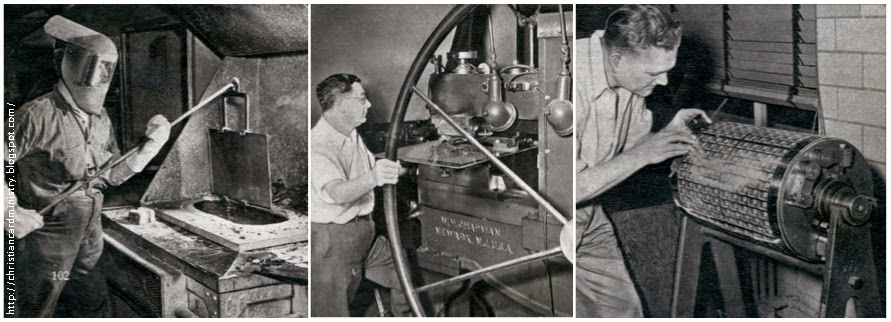

| Fitting bent plate to the rotary cylinder is an exacting job. Plate holds 200 big-size stamps. Stamps about; friendship, everglades and Gold Star Mothers. |

The special postage stamps are called “commemoratives.” In years

past, the com-memoratives have been issued by the authority of the

Postmaster General who also is empowered by law to revise postage-stamp

designs. Much fanfare accompanies the issuing of a commemorative and the

stamp goes on sale the first day at a significantly located post

office. For example, the U.S.-Canada Friendship stamp had a first-day

sale at Niagara Falls, N. Y.; the Will Rogers stamp at Claremore, Okla.,

and the William Allen White stamp at Emporia, Kans. First-day covers,

coveted by stamp collectors, mailed from these post offices usually

number about 450,000. This often means the organization of a special

staff and weeks of preparation for the,big day. The initial printing

order for com-memoratives is usually 50 or 60 million.

Sometimes sales of a special stamp are boomed by an unpredictable

idiosyncrasy. When the three-cent Pony Express commemorative came out in

1940, somebody discovered the pony on the stamp looked like Seabiscuit,

the famous race horse. This caused a furor among collectors and a rush

to acquire the stamp. Then there was the two-cent Grand Canyon stamp

back in 1934. A newspaper carried the story that if the stamp were held

sidewise one could see a perfect profile of Mussolini. The rush was on.

If anyone thinks that getting out a commemorative, or any other kind

of stamp, is a simple operation he is dead wrong. The procedure on the

commemoratives ordered by Congress goes like this: The congressional

authorization is sent to Jesse M. Donaldson, postmaster general; he

sends it along to Alvin W. Hall, director of the Bureau of Engraving and

Printing, who relays the order into the proper channels for processing

in the postage-stamp division and engraving department.

One of four designers in the bureau (who also design all remakes of

paper currency such as the new $20 bill with the Truman back porch on

the White House) makes the layout for the new stamp. This is simplified

if the Post Office Department has sent along subject material for the

design. In the case of the Volunteer Firemen’s stamp, which came out

last October, a portrait of Peter Stuyvesant, founder of the

organization, was submitted. All the designer had to do was secure a

picture of one of the earliest fire engines in this country from the

Library of Congress to use on the stamp with the portrait.

The designers get much of their material from the Library of

Congress, but even this institution occasionally fails them. When

William K. Schrage was working on the Fort Kearny stamp he was surprised

to discover there was apparently no photograph of the early Nebraska

fort anywhere to be found. After days of searching, the Army War College

Library came to the rescue with an old photograph of an original

sketch. This saved the day and the stamp was drawn up with the fort and a

reproduction of a covered-wagon scene from a sculptor’s group over the

doorway of the capitol in Lincoln, Neb.

After the design has been scrutinized by Donald R. McLeod,

superintendent of the engraving division, or his assistant, James T.

Vail, it is then reduced to stamp size by photographing. This photo is

submitted to the Postmaster General for an O.K. When the design has been

approved, the original drawing is sent along to Carl T. Arlt, veteran

foreman of the picture-engraving department. It takes about 120 to 130

hours to make the steel engraving which, of course, is the actual size

of the stamp and is known as the master die. The cutting is done in soft

steel and the design appears in reverse.

The next step is to decide on color. A call goes out to Herbert C.

Tucker, superintendent of the ink-making division, for “pull out” proofs

(actually dabs of color) in several dozen shades. All of the stamp inks

are especially made for steel-engraving work and Tucker keeps

approximately 150 colors on hand. The bureau buys pigments under very

rigid specifications, operating its own testing laboratory and

production lines of mixing, grinding and blending machines. All samples

are matched against standard samples for color and consistency. The

ink-making department, a complete factory in itself, produces 3,000,000

pounds of ink a year for both currency and stamps. All formulas are

secret.

Working with the various samples of ink, proofs of the new stamp are

made from the master die. These proofs, known as die proofs, are

submitted to the Postmaster General who selects the desired color. Then

the master die is hardened. This is done by heating the die in a cyanide

solution to a cherry red at 1400 degrees Fahrenheit and then quickly

cooling it in a brine bath. The hardened master die then goes to the

transfer department where it is placed in a transfer press. Under heavy

pressure this press transfers the cutting on the die to the outer rim of

a soft-steel roll. After hardening, this roll is used to transfer the

design to the steel plates from which the stamps are printed. The plates

are also hardened and if they are to be used on rotary presses they are

bent to fit the cylinders.

|

| Stamps about: Joel Chandler Harris, Palomar Mountain Observatory, Harlan Fiske Stone, U. S. Air Mail. |

Generally, only four plates are made for the special commemorative

stamps. The ordinary three-cent stamp has about 60 plates while only 30

plates are required for the other ordinary stamps. The bureau has eight

sets of plates available for the five-cent airmail stamp.

The men working in the transfer department, whose business it is to

reproduce engravings on steel, are known as siderog-raphers. There are

only 55 siderographers in the United States and nine of them work in the

bureau.

Printing of the stamps is under the close supervision of Jack M.

Smith, superintendent of the postage-stamp division. Any tour of

inspection through this department is under the watchful eye of the

Secret Service. Every sheet or roll of paper used in the printing or

proofing must be accounted for later, either in the form of finished

stamps or scrap which is sent to an agency of the Treasury Department

for verification and destruction by burning. There is no wastepaper to

be thrown away here where any scrap might be a priceless collector’s

item.

Most of the stamps are printed on the nineteen large and nine small

rotary presses. These presses were designed by a former employee,

especially for the job. Each press can turn out about 7800 sheets a day.

If the sheets are for the ordinary variety of stamps they will contain

400 stamps each; if for coil stamps (used in coin machines), only 170,

and if for the book stamps, 360. The majority of the commemoratives are

printed 200 to a sheet. The approximate number of stamps turned out by a

single press in one day is 3,120,000. The total value of stamps turned

out in a day varies, but on many days the figure runs close to

$4,000,000.

|

| Stamps about: Fort Bliss Centennial, William Allen White, Will Rogers and Thomas Edison. |

Printing is also done on flat-bed presses for stamps of limited

demand. Examples are the Canal Zone stamp and stamps of high

denominations such as $1, $2 and $5.

As the long web of stamps rolls from the rotary presses it passes

through a gumming machine and an electric drying chamber. Here the gum

is hardened in 30 seconds. This vegetable gum is not to be confused with

glue and a ”stamp lickers please note” is said to be as pure and edible

as the best food. At the end of the drier the sheets are wound into big

rolls.

The rolls are moved along to machines which perforate the stamps in

both directions and cut the rolls into sheets of 400 or 200 stamps each,

depending on the size of the stamps. These perforating machines are

electronically controlled. Register marks are engraved on the printing

plates and appear on the sheets of stamps in the form of dashes. These

dashes are scanned by an electric eye to hold the paper in proper

position. Formerly, this adjustment was made manually which resulted in

many mutilated stamps.

Every sheet is examined once and counted twice. Where flaws occur it

is possible to salvage as little as a quarter of a sheet, the defective

portions going to the furnaces after being checked by the section of

mutilated paper. The inspected stamps form units of 100 sheets each. The

100-sheet units are stapled in four places on the margins and then cut

into quarter sheets, the size for delivery. These big “books” hold

10,000 stamps of the ordinary size and 20 books make a large package of

200,000 stamps. One of these packages, which is about a cubic foot in

size, is worth $6000 if the stamps are of the three-cent denomination.

Armored trucks carry the packaged stamps daily from the bureau to the

Washington, D. C, Post Office.

Stamps sold in post offices in book form go through a slightly

different procedure. They are stitched in booklets containing 12 or 24

stamps. The stamps for dispensing machines are wound into coils of 500,

1000 and 3000 stamps.

There are almost as many regulations in regard to the printing of any

matter pertaining to stamps as there are to currency. It is illegal to

reproduce a stamp (to illustrate an article such as this) unless the

stamp is less than three fourths of actual size or more than l1/^ times

actual size. One company recently decided to send out in an advertising

brochure a full-color reproduction of all the 1948 commemorative stamps.

The Secret Service, which guards the Post Office Department, went into

immediate action. The brochures were confiscated and so were the plates

from which they were printed and action in the federal courts was

threatened. That company learned the hard way that Uncle Sam is mighty

particular about anything concerning his stamp factory.

|

| Stamps about: Moina Michael, Rough Riders, Swedish Pioneers, Indian Centennial , Fort Kearny, Progress For Women |

|

| Stamps about: Lincoln, Juliette Gordon Low, Clara Barton, American Poultry, Volunteer Firemen, Youth Month |

No comments:

Post a Comment

Welcome, I publish commentary closely connected to the topic. Thank you for participating.